How Kubrick’s Vision for Barry Lyndon Led Him to NASA

Stanley Kubrick was known for his meticulous attention to detail and his quest for innovative ways to achieve the exact visual style he envisioned for his films. On the set of Barry Lyndon (1975), his epic period drama, Kubrick went to extreme lengths to create an authentic, painterly look that would accurately evoke the 18th-century setting. One of his most groundbreaking choices was to use special lenses developed by NASA to shoot scenes lit only by candlelight, a feat that had previously been impossible with conventional film technology.

Kubrick wanted Barry Lyndon to look and feel as though it were a window into the 1700s, with the lighting mimicking natural sources from the time period—candlelight, daylight, and firelight. However, shooting interior scenes lit only by candles presented a major challenge. Standard film lenses weren’t sensitive enough to capture clear images in such low light, and adding artificial lighting would destroy the authenticity of the look he wanted. Kubrick needed a lens with an extremely wide aperture to allow enough light onto the film.

Normally, candlelit scenes are augmented by orange-gelled lamps just out of frame, but Kubrick insisted that the candles themselves be the sole light source. However, candles provide very little light — measured in "foot-candles," a unit that refers to the illumination cast by a candle from one foot away. In the case of Barry Lyndon, scenes required around three foot-candles to properly illuminate the actors’ faces. Using conventional 1970s film technology was challenging because the film stock of that era, rated at an exposure index (EI) of 100, wasn’t sensitive enough to capture low-light scenes well. Even after pushing the stock to an EI of 200, there still wasn’t enough light. To make up the difference, Kubrick used special lenses with an extreme aperture of T0.7 — the widest ever created, originally developed by NASA to photograph the dark side of the moon. This setup allowed him to capture the candlelit scenes with unprecedented clarity, making the visuals one of the film’s most iconic achievements.

Kubrick’s solution was to acquire ultra-fast lenses that had originally been developed for NASA by Carl Zeiss. These lenses were designed to photograph the dark side of the moon and had an aperture of f/0.7, which was one of the largest ever made. The f/0.7 aperture allowed a significant amount of light to enter the lens, making it possible to capture clear images in extremely low-light conditions.

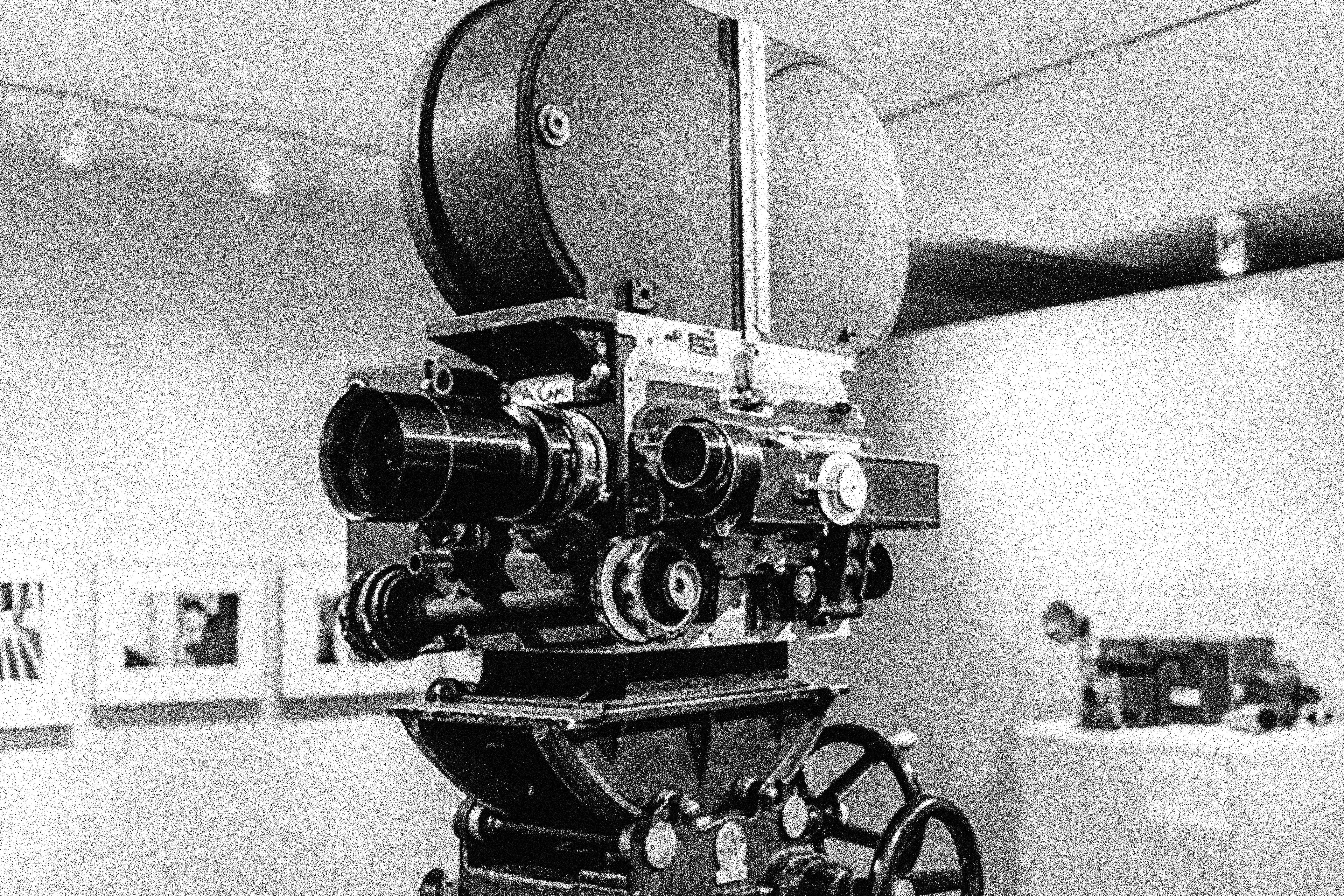

Kubrick’s team modified these lenses to fit his Mitchell BNC camera, and by doing so, he gained the ability to shoot scenes in candlelight with a level of clarity and richness that had never been seen before. It allowed him to achieve an immersive look that looked more like oil paintings than traditional film, as Kubrick avoided the harshness of artificial light sources in favor of the warm, natural glow of candles.

Technical Specifications

Aperture: f/0.7 (maximum)

Focal Length: 50mm

Lens Construction: 8 elements in 6 groups

Image Circle: Designed for a 35mm frame

Minimum Focus Distance: Approximately 2 feet (0.6 meters)

Mount: Originally custom-built for NASA; modified for Kubrick's Mitchell BNC camera

Weight: Approximately 5 pounds (2.3 kg)

Only Ten Made

There were only ten Zeiss 50mm Planar f/0.7 lenses produced. One was retained by Zeiss, six were sold to NASA for space exploration photography and three were purchased by director Stanley Kubrick for the production of Barry Lyndon.

Designed for NASA:

The 50mm f/0.7 lens was originally developed by Carl Zeiss for NASA in the 1960s. Its primary purpose was to capture images of the far side of the moon during the Apollo missions. This extremely wide aperture allowed it to capture images in very low-light conditions, essential for photographing lunar landscapes that were barely illuminated.

Additional Modifications

Once the modifications to the Zeiss 50mm f/0.7 lens were completed, extensive testing and recalibration followed. The focus scale had to be meticulously calibrated due to the extremely shallow depth of field, demanding high precision.

While the 50mm focal length was ideal for close-up shots, Kubrick sought a wider option. To achieve this, he sourced an adapter originally intended for adjusting cinema projector lenses. This adapter, when mounted on one of the 50mm lenses, provided an effective focal length of 36.5mm with only minimal light loss. Though a 24mm adaptation was also attempted, Kubrick found its distortion unacceptable, ultimately deciding against its use.

The result was a series of breathtaking scenes that have become some of the most iconic in film history. The candlelit sequences in Barry Lyndon have a soft, diffused glow that perfectly captures the ambiance of the 18th century. Kubrick’s use of these NASA lenses transformed what was possible in cinematography, influencing filmmakers and cinematographers for generations to come. His innovative approach demonstrated how new technology could be harnessed to push the boundaries of visual storytelling, and it is still celebrated as one of the most daring and creative uses of technology in film.

Kubrick’s work on Barry Lyndon showcases his dedication to capturing historical authenticity and his relentless pursuit of innovation. By using these NASA lenses, he broke new ground in cinematography and left an indelible mark on the film industry, proving that sometimes, in order to go back in time, you have to reach for the stars.