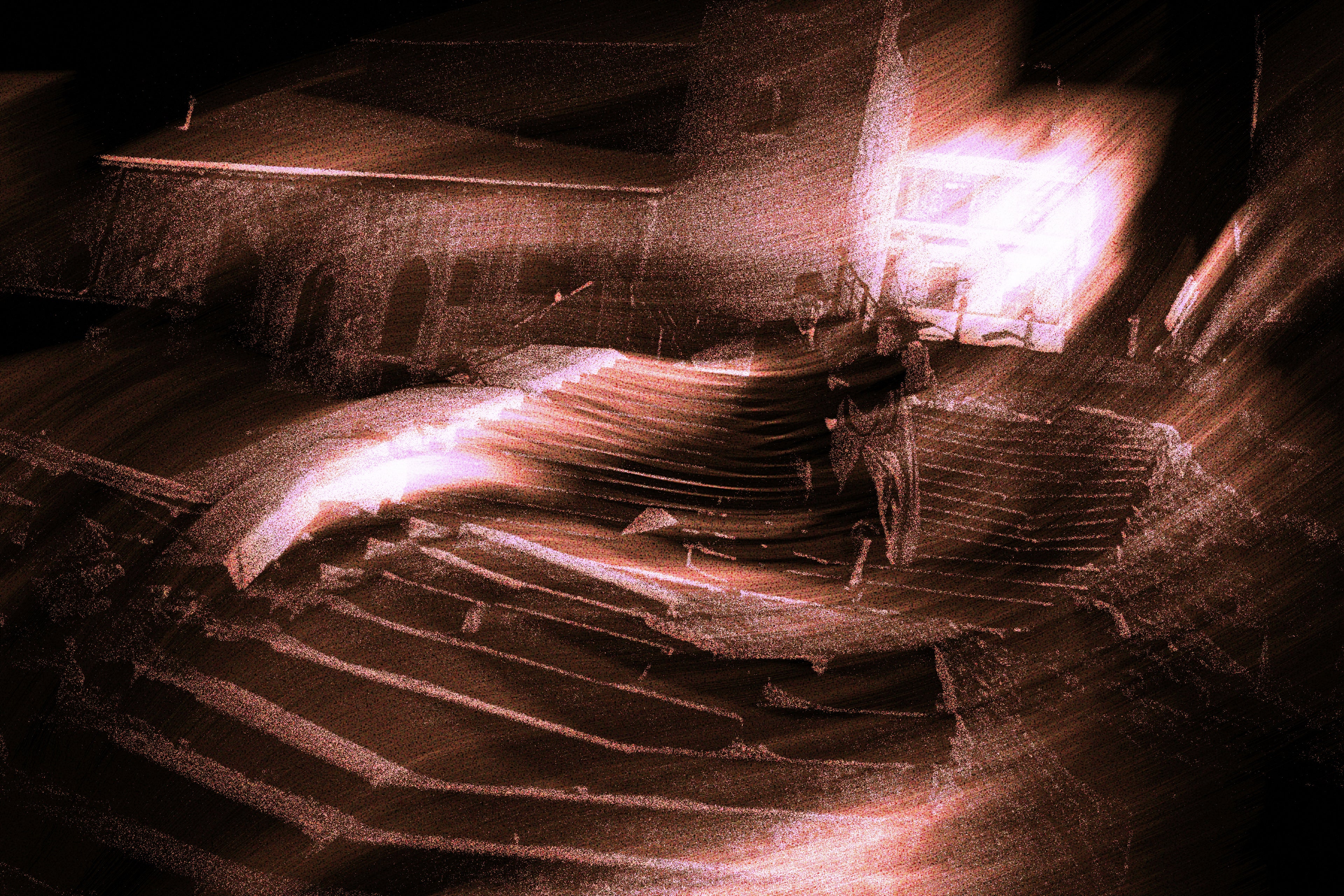

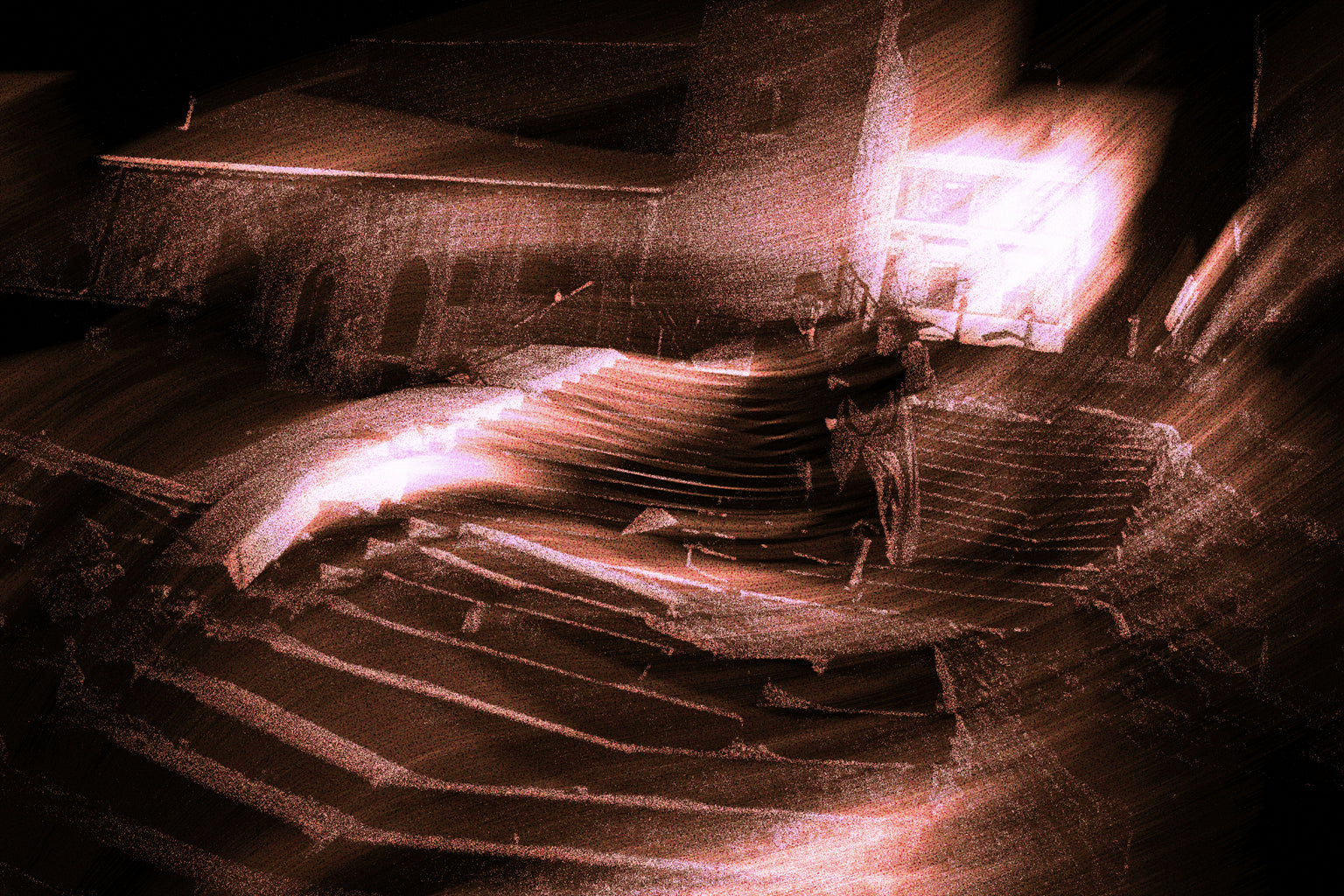

The Dutch angle actually traces back to Deutsch, the German word for “German.” The technique was a hallmark of German Expressionist cinema in the 1920s—a movement that thrived on stylized visuals, distorted sets, and psychological depth. Films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922) leaned into unsettling imagery, and the tilted frame was used to reflect a character’s unstable mental state or to heighten dreamlike tension.

When these films began influencing filmmakers outside Germany, the term “Deutsch angle” morphed...perhaps through mistranslation or mishearing, into “Dutch angle.” The name stuck, even as its true origin became a cinematic footnote.

he Dutch angle remained a cinematic oddity until it found new life in mid-century thrillers and film noir. Directors used the tilt to mirror paranoia, danger, or moral ambiguity. In the 1949 film The Third Man, Carol Reed used the Dutch angle throughout to reflect post-war disorientation in Vienna, famously stating that the tilted shots captured a “world out of joint.”

In Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), the tilt helped depict the dizzying effects of fear and obsession. For filmmakers, it became a tool not just of visual interest, but of emotional storytelling, subtly shifting the audience’s perspective, literally and figuratively.

Today, the Dutch angle has a permanent, yet sparingly home in the filmmaker’s visual toolbox. It’s a favorite in horror (The Shining), sci-fi (Thor), action flicks (Mission: Impossible), and even arthouse indies.

In the 1990s, the technique saw a resurgence as stylized filmmaking became more prominent across genres. Directors like Michael Bay and Joel Schumacher used it to inject energy and unease into action and comic book films like Armageddon and Batman Forever. It also appeared in psychological thrillers like Se7en and sci-fi films like Twelve Monkeys. Spike Lee used it in Do the Right Thing to turn up the heat both literally and metaphorically during moments of rising tension. While it’s sometimes overused (hello, Battlefield Earth, with 90% canted shots), when employed with intention, the Dutch angle still delivers emotional weight and visual impact.

There’s something primal about seeing the world tilted. Our brains crave balance and symmetry. When that balance is disrupted, we instinctively sense that something is wrong. The Dutch angle doesn’t shout. It whispers. It suggests imbalance, tension, unease, and psychological instability, all without a single word spoken.

From the shadowy alleyways of German Expressionism to the explosive set pieces of modern blockbusters, the Dutch angle continues to evolve. It proves that even the smallest shifts in perspective, just a few degrees of tilt, can forever change how we experience a story. Sometimes the best way to tell the truth is to turn the camera sideways.